Old friends and new faces at NDB2025

Examining diseased comb

Hard at work in the lab

Disease inspections in Rona's apiary

NDB COURSE 2025

The Examination Board for the National Diploma in Beekeeping was established in 1954 to meet the need for a beekeeping qualification above the level of those awarded by the British Beekeepers Association and is the highest level beekeeping qualification available in Britain.

The NDB Board holds an annual 5-day advanced beekeeping residential course at Pershore College. Around 12-15 students are accepted on the courses which run on a 3-year cycle. Up to 4 NDB qualified tutors are always on hand, plus visiting lecturers from a range of disciplines who are all recognised experts in their fields. This was my second course, having attended one in 2023.

The examination for the diploma takes place every 2 years and consists of a series of tests including:

- a written assignment

- a 3-hour written paper

- preparation of a portfolio of beekeeping experience

- a portfolio of plants and insects of relevance to beekeepers

- a practical assessment involving bee handling, disease recognition and general biology

- a viva voce including a presentation on the assignment and a short spontaneous presentation.

The course is intensive with sessions in the classroom, laboratory and apiary all day and into the evenings. Each attendee has to give a presentation on a subject decided by the directing staff on an unusual or obscure topic for which a lot of research in scientific papers is needed. My studies at Cornell University were a big help in shaping my approach to my allocated topic.

The participants are people of all ages, from all parts of the country and different walks of life and are either Master Beekeepers or, in my case, have completed all the BBKA Modules and hold the Advanced Theory Certificate and the General Certificate in Beekeeping Husbandry. I will take the Microscopy Certificate in November and Master Beekeeper Assessment next year.

The old saying that the more you learn the less you know certainly applies to the NDB Programme; when you are used to being one of the most knowledgeable people in your local or county beekeeping association, you come down with a bump when you meet a dozen or so people who know much more than you.

Whether you decide to take the exam or not is up to the individual candidate. The decision depends on the amount of time you are prepared to spend on building the portfolio, which involves many hours of meticulous collecting of insects, flowers, pollen and honey bee dissections – all beautifully mounted and presented to a high professional standard.

One of the benefits of attendance is the opportunity to meet like-minded people from all over the country and to share knowledge and experience with them. The contacts I made last time proved very useful on a number of occasions when I need help or a contact in another part of the country.

Overall, an intensive, demanding course that stretches your mind and opens new horizons in your beekeeping life.

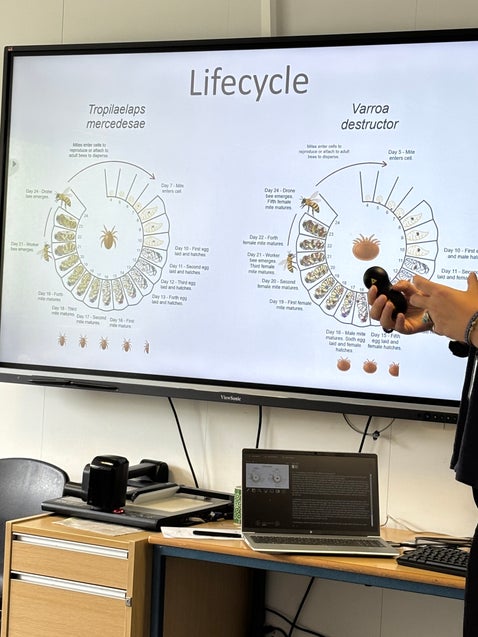

Lecture on Tropilaelaps by Maggie Gill from APHA

BLOG SUMMER 2025

We’re into July already and the summer flow is full on with Bramble and Lime in bloom. The

warm, sunny weather has helped to stimulate nectar production, and plants or trees with

deep roots can still find plenty of moisture. Other sources may soon start to suffer from

drought stress and stop producing nectar unless we some have rain.

In the Teaching Apiary we have taken off the spring harvest and, I suspect, the beginning of

the summer crop. The honey we have extracted is medium/dark in colour with a good nose

and a very persistent, complex flavour in the mouth, possibly due to the amount of Horse

Chestnut the bees have foraged. When we took off supers of honey we replaced them with

empty ones to give the bees space and avoid overcrowding.

Any profit from honey sales this year will help to offset the cost of setting up the apiary, and

towards the cost of equipment and consumables such as feed supplements, varroa

treatment and foundation.

It’s still not too late for colonies to swarm so we are being vigilant during weekly inspections,

keeping a sharp lookout for the signs of swarm preparation, creating space for the queen to

lay and for the foragers to bring in their bounty. Remember one frame of brood produces

three frames of bees and the foragers who are out at work all day need somewhere to sleep

at night.

With the threat of European Foul Brood (EFB) on our doorstep in Hampshire we are paying

careful attention to apiary hygiene and examining every brood frame for signs of something

amiss with the larvae. Collected swarms from an unknown origin are a risk and should be

kept away from other colonies until they have a clean bill of health before being installed in

an apiary with other colonies. When the disease first strikes there may be only one or two larvae affected and is very easy

to miss.

There are a lot of wasps around already. They are normally in the carnivorous stage of their

life cycle and don’t start scavenging for sugars until late summer or early autumn, but these

are after anything they can get. Wasps can rob out a weak colony very quickly, so we need to

ensure that our colonies and nucs have a lot of bees to fight their corner, uniting weaker

units if necessary and reducing entrances to the smallest setting.

We still have time to raise some new queens. An easy way is to do a split from a strong

colony into a nuc. The nuc will have time to build up a good-sized population before winter.

In the teaching apiary we will be doing a batch of grafts on Sunday 13 July and hoping for

good weather when the new queens emerge and embark on their mating flights.

Now is a good time to think about uniting weak colonies, to have a big foraging force for the

summer nectar flow, and for going into winter. Weaker colonies are always at risk of winter

failure, so it is better to have one colony that survives than to have two that perish before

next spring.

Varroa populations will be building up at an alarming rate now. We are testing all our

colonies using the CO2 method and taking appropriate action to reduce the varroa load if

the test result is greater than 1%. Testing for Varroa Sensitive Hygiene (VSH) behaviour

continues. We have one promising colony from which we’ve taken a split to continue the

genetic line. If they continue to show resistance, we will take some grafts and produce more

queens with this trait.

Thank you to everyone who has supported the teaching apiary this year so far and well done

those of you who passed the Basic Assessment this year.

Good luck with the rest of the season and happy beekeeping!

Alan Baxter

2 July 2025

www.alanbaxtersblogs.co.uk

QUEEN REARING COURSE 14-15 JUNE 2025

This was Philip Latham's second weekend event at his training apiary in the New Forest and he asked me and another two experienced beekeepers to be tutors on the course. There were 20 trainees who enjoyed a feast of beekeeping skills and learnt a lot about how to select and breed their own queens. Here's a shot of the course at the end

DEALING WITH AN AGGRESSIVE COLONY

In early May one of the colonies in my teaching apiary started to display excessive defensive behaviour, following and stinging people for about 100 metres from the hive. I practice a zero-tolerance policy for this kind of behaviour for the following reasons:

- It is very unpleasant for me and for the people who come to the apiary to learn.

- It is bad for relations with the neighbours and members of the public passing by.

- The drones carrying the aggressive gene will mate with young queens from the area and pass on the bad behaviour to other beekeepers’ colonies.

The genetic line from which this colony was raised has so far been faultless. The colonies in my home and teaching apiaries are well known for their gentleness and calmness on the comb.

The queen was bred by me last year and until recently was being considered as an egg donor for queen raising this year.

Apart from genetic reasons, colonies can turn aggressive when there is a sudden end of a nectar flow, when robbing is taking place, when they are invaded by pests, when disturbed by noise or clumsy handling by the beekeeper. None of these conditions were present.

Varroa testing by CO2 produced only one mite from a sample of 300 bees. There were no signs of adult or brood diseases.

Recently, the Kakugo virus (KV), which was only detected in the brain of aggressive workers of Italian bees by real-time PCR, was suggested to trigger behavioural changes in honey bees1. My bees are not Italians, but there has been so much hybridisation that it’s impossible to know if there is any trace of Italian stock in their lineage. It’s a long shot, but it could explain the mystery of why a well-behaved colony turned nasty for no apparent reason.

Actions

The actions I took, with the help of leaners in the group, were as follows:

6 May Couldn’t find the queen.

Destroyed all the capped drone cells.

Split the colony in two with the brood and young bees in a new separate brood box.

United the new brood box with a calm colony by the newspaper method.

11 May Uniting complete, combined colony calm and gentle.

11 May Found the queen in the parent colony and killed her.

We did this by moving the brood box a few metres to one side to bleed off all the flying bees then divided the brood frames into twos.

Destroyed all the capped drone cells.

18 May Destroyed all the queen cells.

19 May Now hopelessly queenless, the remaining colony was united with a different colony by the newspaper method.

26 May Uniting complete, colony calm and gentle.

Conclusion

Both colonies are calm and strong in numbers, building up for the summer flow.

It was possible to deal with an aggressive colony by:

- splitting up the flying bees from the nurse bees

- killing the drone brood to prevent the aggressive genes from being passed on during mating,

- culling the queen.

- uniting them separately with other colonies.

Reference:

- Deformed wing virus is not related to honey bees' aggressiveness. Agnès Rortais, Diana Tentcheva, Alexandros Papachristoforou, Laurent Gauthier, Gérard Arnold, Marc Edouard Colin& Max Bergoin Virology Journal volume 3, Article number: 61 (2006)

Alan Baxter

10 June 2025

QUEEN INTRODUCTION

It’s the time of year when beekeepers are buying in new queens and are faced with the uncertainty of whether or not the queen will be accepted in her new colony. The following method was first described by L.E. Snelgrove ¹ in 1940 who claimed an almost 100% success rate.

The method is based on the principle that the new queen should adopt the receiving colony’s odour before being introduced.

The colony should be showing signs of queenlessness before carrying out the operation; this usually takes from a few minutes to as much as half an hour after removal of the old queen.

The “one-hour’’ method

- Release the bees escorting the new queen from the cage in which they arrived.

- Take a matchbox and place it three-quarters open over brood comb in the receiving colony at a point where the bees are thickest.

- Gently close it with about 20 bees inside.

- Put a pin through the side to keep it closed and put it in your pocket for 5 to 10 minutes.

- At the end of this period partly open the box with your thumb over the opening and drop the new queen in among the bees.

- Close the box leaving a very narrow opening for ventilation, put in the pin and return it to your pocket for half an hour.

- The bees confined in the dark with no food will be more interested in trying to get out than the presence of the new queen.

- The queen and the bees will soon have the same odour thanks to the warmth in your pocket.

- Give a little whiff of smoke through the hole in the crown board to clear the way.

- Place the matchbox upside down over the hole in the crown board and open it gently

- The new queen and her new escort will then safely make their way down into the queenless hive.

- Close the hive and don’t disturb for a few days.

Essential points :

- The queen acquires the odour of the hive before being introduced.

- She is hungry when she enters the hive.

- She enters the hive accompanied by a friendly escort.

- The hive is in a state of distress and looking anxiously for their queen.

¹ L.E. Snelgrove The Introduction of Queen Bees Furnell & Sons Aug 1940

by Alan Baxter

QUEEN TRAPPING

Queen trapping is a technique used to induce a brood break in a colony for the purpose of controlling the Varroa mite population. Over a period of 36 days, the queen is trapped on a series of frames that are used as bait frames to attract and trap Varroa mites. The capped brood frames are then destroyed, thus resulting in a decrease in the mite load in a colony. Instructions for the procedure are at Annex A

Varroa mites reproduce inside honey bee brood cells. Trapping the queen in a cage can prevent her from laying, which induces a brood break in a colony and reduces the mite population in the colony by slowing their reproductive rate. However, mites can survive on adult bees for many weeks until bee brood is present in the colony again and the mites can resume reproduction. However, if the queen is restricted to laying on a single frame at a time, availability of honey bee brood is tightly controlled. These frames can be used as bait frames to attract the mites into the brood cells where they are capped over and can then be removed from the colony culling the Varroa mites. The use of bait frames in this version of the queen trapping method ensures the maximum efficacy of using queen trapping to reduce the mite numbers in the colony.

A brood break offers a good opportunity to eradicate the majority of mites in the colony if it is combined with an oxalic acid treatment1. Oxalic acid-based medication is not suitable when there is brood in the colony because it is lethal to open brood and cannot penetrate the wax cappings to kill mites in capped brood cells. However, oxalic acid-based medications have an efficacy of nearly 90% against mites living on the adult bees2 and, as there is nowhere else for them to go in a broodless colony, this combination can result in the removal of the vast majority of mites from the colony.

The bees’ ability to synthesize the glyco- protein vitellogenin is essential for brood jelly production and for winter survival and is impeded in adult worker bees that have been parasitized by the varroa mite in the pupal stage3. When vitellogenin is not used to produce high-quality brood food, the high vitellogenin and low juvenile hormone titre makes the bee a longer living bee, i.e. the winter bee3,4.

The procedure requires a certain degree of beekeeping skill, and the timing must be carefully judged to avoid leaving the colony short of foragers for the main nectar flow, and a lack of drones for mating. The advantages and disadvantages of this method combined with oxalic acid treatment are:

Advantages:

- Up to 90% efficacy

- No chemicals required

- Because there is less brood to care for, more bees are foraging so a higher honey yield is possible

- Queen is less liked to be superseded when caged on frame and continues laying than when confined to a small cage and prevented from laying

- Longer-living winter bees

- Realistic method for small-scale hobbyist

Disadvantages:

- Time consuming and requires 5 visits to colony

- Requires beekeeper skill and queen handling

- Requires a timetable and relies on exact timing of manipulations

- Potential weakening of colony if applied too late in the season

- A less attractive method for commercial bee farmer.

Conclusion

Queen trapping combined with Oxalic acid treatment is an effective method of varroa control for the hobbyist beekeeper. Due to the time taken and the extra equipment required it is unlikely to be an attractive option for the commercial bee farmer.

- Anastanov, M., (2020) Queen Trapping and Queen Caging, BBKA News Special Series Issue, Integrated Pest Management, April 2020.

- Büchler, R., Uzunov, A., Kovačić, M., Prešern, J., Pietropaoli, M., Hatjina, F., ... and Nanetti, A. (2020). Summer brood interruption as integrated management strategy for effective Varroa control in Europe. Journal of Apicultural Research, 59. DOI: org/10.1080/00218839.2020.179327clonc,s

- Altered Physiology in Worker Honey Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Infested with the MiteVarroa destructor(Acari: Varroidae): A Factor in Colony Loss During Overwintering? Gro V. Amdam , Klaus Hartfelder , Kari Norberg , Arne Hagen , Stig W. Omholt. Journal of Economic Entomology, Volume 97, Issue 3, 1 June 2004, Pages 741–747,

- Jozef van der Steen & Flemming Vejsnæs (2021) Varroa Control: A Brief Overview of Available Methods, Bee World, 98:2, 50-56, DOI: 10.1080/0005772X.2021.1896196

SHOOK SWARM

The colony that was kindly donated by David Marsden, a former FDBKA member, has completed its quarantine. It has been treated with Oxalic Acid for phoretic varroa and passed a health and temperament assessment before being moved to the Training Apiary 10 days ago. This is the same procedure as for a collected swarm of unknown origin.

An inspection on Sunday 23 March revealed a colony in great need of a complete change of equipment. Many of the brood frames were rotten and broke easily, and the whole brood box was bunged up with propolis, brace comb and honey.

It was decided a shook swarm should be done as soon as the weather is warm enough.

Why Shook Swarm?

Shook swarms are carried out on colonies that need a complete change of comb or have a high level of Chalkbrood infection. It is also a treatment for low levels of EFB that may be ordered by the Bee Inspector*

The benefit is that the colony starts again in a completely new home that is varroa-free and without of all the debris and accumulated detritus that older comb contains. Shook swarmed colonies are said to take to grow much more vigorously afterwards.

It is only suitable for colonies with at least 6 seams of bees and enough young bees 10-20 days old to draw out the large amount of comb required. A feed of thick sugar syrup is needed, even if there is a nectar flow. Smaller colonies can be shook swarmed into a nuc.

Shook swarm can be done between March and July. However, all the brood is lost, so shook swarm should not be carried out in the weeks before the main nectar flow as there won’t be enough foragers to benefit from it.

Equipment

- Clean floor

- Queen excluder

- Foam entrance blocker

- Clean brood box

- 11 frames of foundation

- Crown board

- Rapid feeder

- 5 Litres thick syrup

- Roof

- Large bin bag for old frames to be destroyed.

Method

- Move the hive to one side

- Clean the ground underneath of any debris

- Add the clean floor

- Add the queen excluder

- Add the brood box. The flying bees will return to this box.

- Close the entrance with the foam blocker to keep the bees in the box.

- Put in the frames of foundation leaving out 4 frames in the middle

- Go through the original brood box and find the queen

- Cage the queen for safe keeping and keep her warm in your pocket

- Remove the frames from the original box one by one and shake the bees off with a sharp tug taking care not to knock the frame on the side of the box.

- Any bees still clinging to the frame can be lightly brushed or stroked off with the back of your hand or with a leafy twig (not a bee brush which can damage the bees and collect dirt or infection).

- When all the bees are in the new box carefully put the remaining frames in the space and let them sink down on their own. Do not push them down.

- Release the queen onto the new frames. Do not forget and take her home!

- Remove the entrance blocker to allow the flying bees to come and go.

- Add the feeder and syrup.

- Put on the crown board and roof.

Follow-up

- Once comb is drawn, and the queen has started to lay, the queen excluder can be removed.

- They need to be supplied with syrup until all the frames have been drawn out.

- Bees can’t draw comb next to the wall of the hive so the end frames should be turned round once one side is drawn.

- Supers can be put on once all the frames have been drawn out, but not before or they will start to work on the supers.

- Oxalic acid treatment can be given before any brood is capped. The colony will then be practically varroa-free.

Alan Baxter

27 March 2025

WINTER & SPRING LOSSES

Many beekeepers suffer colony losses in winter and early spring and wonder what happened.

Most losses are avoidable so let’s have a look at some of the common reasons why colonies die

out, how we can prevent it and what we can do to help colonies that are vulnerable.

Health

It is important to carry out a full health inspection of the adult bees and the brood after the

summer harvest. A health inspection is a visit to the colony in its own right and not combined

with other work. Learn to recognise what healthy bees and brood should look like, and how to

detect when something is wrong. The BBKA pocket guide on honey bee health is an excellent

addition to the beekeeper’s tool kit.

Starvation

This happens when the colony runs out of food and there is no foraging to bring in stores. This

could be because:

• the beekeeper was greedy and took all the colony’s honey the previous summer.

• a genetic factor whereby the bees naturally eat a lot of food.

• a mild winter when the bees are very active and need more food for work.

• The queen continues to lay and more food is needed to feed the larvae.

• There are stores but the bees cannot reach them (isolation starvation).

Prevention

• Ensure you leave enough stores for the winter. An average colony needs about 20kg of

honey to last until the following spring. That means several frames of capped stores in

the brood box and at least one full super.

• If they have less than this in October, feed with 4 litres of thick sugar syrup.

• Remove the queen excluder so the cluster can go into the super and not leave the queen

behind to die.

• Heft the hives every 2 weeks and top up with fondant if needed.

• Give pollen supplement e.g. Candipolline and fondant in February to provide nutrition

for the larvae and to stimulate the queen to lay.Varroa

Varroa

If the varroa load is high it will bring stress on the bees in winter by feeding on their fat bodies

and exposing them to fatal viruses such as Deformed Wing Virus (DWV) or Chronic Bee Paralysis

Virus (CBPV).

Normally in winter there is a period of no brood, and the mites cannot reproduce. If the winter is

mild and the queen keeps laying, there is no brood break, the mites continue to reproduce in the

brood cells and to grow exponentially.

Prevention

Varroa treatment in late summer and in early December, followed by monitoring to check the

success or not of the treatment, must be carried out strictly in accordance with the

manufacture’s instructions and recorded on VM2.

If the numbers of varroa in summer are too high, the population of mites will continue to grow as

the number of bees declines, to the point where the colony is overwhelmed.

Small colonies

If the colony going into winter is small, they won’t have enough bees to look after the queen and

to keep the brood nest warm. The queen will die and the colony will dwindle and perish.

Prevention

In autumn, unite weak colonies that have less than 5 frames of brood or put them in a nuc which

is easier to keep warm. Give stimulative feeding of thin syrup in September to encourage the

queen to produce more winter bees, then thick syrup to lay down as stores.

Queen failure

A colony that loses its queen in autumn or winter won’t be able to replace her with a new mated

queen and the colony will dwindle and die.

Prevention

Change queens that are more than 2 years old for a new queen. If the old queens are good ones

and you can’t bear to part with them, ‘retire’ them to a nuc and use them for breeding new

queens next year.

Always use locally bred queens from stock that is adapted to the local environment. Buying

queens imported from another country or a different part of the UK is a recipe for failure.

Nosema

If nosema is present in summer, the bees can defaecate outside the hive and, in a strong colony,

the disease will often go unnoticed. However, nosema reduces the bees’ ability to absorb

protein, so the bees are weaker and have shorter lives. Come autumn and winter the bees are

confined to the hive, the spores spread more quickly, the number of bees is reducing but the

nosema spores keep increasing, leading to winter losses or failure to build up in spring.

Prevention

Test for nosema after the summer honey harvest. Send a sample of about 30 bees to a

laboratory or a beekeeper who has microscope, for testing. Alternatively, kill a few bees and pull

out their intestines with fine tweezers. The midgut should be yellowy-brown, if it’s white and

fragile nosema is probably present.

Remedy

There is no treatment. The spores are deposited in the comb, so put them on clean comb using

the Bailey comb change for a weak colony procedure, then feed them with 2:1 sugar syrup and

pollen supplement and hope for the best.

Equipment:

• Clean brood chamber containing frames of sterilised drawn comb

• 4 Dummy boards

• Queen excluder and eke with entrance block or a Bailey Board.

• Crown board

• Floor

• Contact feeder and 2:1 sugar syrup.

Method: Day 1

• Take the frame with the queen on and place it in the new brood box.

• Remove all frames without brood from original brood box and any supers.

• Close up the remaining frames in the centre of the brood box with dummy boards.

• Put frames of new drawn comb in the new box on either side of the frame with the

queen.

• Match the number of drawn combs with the number in the bottom box.

• Close up the space in centre of the new box with dummy boards.

• Put a queen excluder and an eke with an entrance block (or a Bailey Board if you have

one) on the old brood box.

• Close the lower entrance.

• Place the new brood box with clean drawn frames above the lower brood box.

• Put on the clean crown board.

• Feed with 2:1 sugar syrup.

• Add the roof.

• Dispose of the old comb by burning.

• Scrape and disinfect by scorching the old frames.

Day 7

• The queen in the upper box should have moved onto the new frames and started to lay.

• Remove the old frame with the remaining brood and return it to the bottom box.

• Add more drawn sterilised frames to the new box and close up with dummy boards.

• Check lower box for queen cells and remove if found.

• Remove any frames that have no brood.

• Dispose of the old comb by burning.

• Continue to feed.Day 7-28

• Add a few more drawn sterilised frames in the top brood box.

• Remove frames with no brood from the bottom box.

• Dispose of the old comb by burning.

• Replenish the feed.

Day 28

• Place a clean floor on the stand and add an entrance blocker.

• Put the upper box on the new floor and adjust the entrance.

• Add a queen excluder then the super(s).

• Close the hive with the clean crown board and the roof.

• Remove, scrape and disinfect the old queen excluder and upper entrance or Bailey

Board, lower brood box and old floor.

• Dispose of old comb by burning .

20 February 2025

25 January 2025

THE APIARY IN JANUARY

The days are getting longer and lighter, birdsong is in the air, there’s a growing sense of the earth

awakening, reenergised after a long sleep. The winter bees in the darkness of their hives can feel

this change and they are starting to prepare for spring. On milder days they will venture out on

cleansing flights and to forage for pollen on Hazel, Willow, Snowdrops, early Crocus and Garrya

elliptica. The incoming pollen will stimulate the queen to lay eggs and the winter bees will start

to be busy again, feeding the larvae and keeping them warm.

During the coldest days of winter, the colony will have formed a cluster around the queen,

maintaining a core temperature of about 18 deg C while they are broodless. The bees on the

outside of the cluster or mantle, can tolerate temperatures as low as 8 deg C before they fall off

and die. However, once there is brood the colony must raise the temperature of the brood nest

to 35 deg C. They generate heat by a sort of shivering where they flex the big powerful flight

muscles in the thorax without moving their wings. See figure 1 below.

Some beekeepers note that their colonies are never broodless which puts an extra strain on the

winter bees who must keep the brood nest at 35 deg C and feed the young larvae. They eat

carbohydrate in the form of honey or sugar as fuel, so it’s important to check the weight of the

hives regularly by hefting to make sure they have enough stores.

Apart from ensuring the hives are secure against the storms, checking that they have enough

food, and topping up with fondant if required, there’s not much for the beekeeper to do in the

apiary. In the bee shed it’s worth checking any stored supers to see if the wax moth treatment

needs to be repeated, and all the usual winter jobs of repair and maintenance of equipment,

making up new, or refurbishing old frames with fresh foundation ready for the coming season.

Spring is just around the corner and will be upon us before we know it. Look out for the next blog

with tips and hints for the coming weeks when we look at the first inspection of the year.

Robbing has been a serious problem in the queen rearing apiary this autumn. After bemoaning the lack of wasps, we were suddenly inundated with thousands of hungry blighters who were determined to get into the more vulnerable nucleus hives (referred to in the jargon as nucs). They even started chewing holes in the back of the nuc boxes just to get at the precious stores of honey that would feed the little colonies of bees in the coming winter. Sadly the stress of defending the hives against the invaders proved too much for one of the nucs and it gave up the ghost.

Wasps have an important role to play in our already fragile ecosystem and I am very reluctant to put out traps, but the consequences of losing whole colonies of bees to wasps who are going to die in the next couple of weeks, are too serious to ignore. Traps that allow non-target species, such as the delicate hover fly or precious moths, to escape can reduce the collateral damage amongst innocent bystanders.

Which leads me to the thought about Asian Hornets, which are a sort of wasp. If Vespa vulgaris has made a sudden late appearance, will Vespa velutina do the same......?

15 October 2024

Exciting day yesterday

WINTER PREPARATION

“In the life of the honey bee there are only 2 seasons – winter and preparing for winter”

Introduction

The honey bee colony builds up to its maximum foraging force in July for the summer flow when they must accumulate enough food stores to last for the next 7 or 8 months. The population of ‘summer’ bees rapidly declines from now on until there only remains a small number of ‘winter’ bees. Unlike summer bees, who only live for 5 or 6 weeks, the winter bees can live for up to 6 months. Their job is to keep the queen alive and ready to start producing brood again in a few months’ time, as well as to feed the spring larvae. Colonies can be lost in the spring when not enough winter bees have survived to keep the colony alive. The more winter bees, and the longer they live, the greater the chance of the colony surviving into the following year.

Feeding

Stimulating the queen to lay

Worker bees born in August and September and will die in November but those born after the beginning of October will live until next spring. It is vitally important therefore that the queen continues to lay after the summer peak to produce plenty of heathy, well-fed winter bees. This can be achieved by stimulative feeding of thin 1:1 sugar syrup, and pollen patties if there is little pollen coming in, in September to simulate a nectar flow and help the queen to keep laying. Note that thick 2:1 syrup will only be laid down as stores.

Winter stores

The average colony is estimated to need about 21kg of honey to avoid starvation. Happily for us, the bees usually collect more than they need and the surplus provides us with the delicious honey that we enjoy so much. If we take more, or if the bees haven’t collected enough, we have to replace it with some form of artificial feeding, usually in the form of sugar syrup, pollen supplement or substitute, and fondant.

Hefting the hives regularly in winter can tell us if they have enough. If the hive feels light, feeds of thick 2:1 syrup can be given as long as the daytime temperature is above about 10 deg C. Thereafter fondant is required.

Some beekeepers leave the bees with a full super. It’s important to remove the queen excluder so the queen isn’t isolated when the cluster moves into the super. Whether the super is placed under or over the brood box doesn’t seem to make any difference, although bees will often prefer to move upwards, so it could be argued that above is better. In some cases, the cluster will not move up and over the top of the frames to reach the stores in nearby frames and the colony dies in what is known as isolation starvation. Communication holes made in the comb can help the cluster to move more easily from one frame to the next.

Health

A thorough health inspection after the supers have been taken off can give a warning of any adult or brood diseases which can then be treated, hopefully in time. See below on where to find more information on pests and diseases.

Varroa

Varroa infestation is one of the main causes of winter losses and must be treated now.

Although the bee population is decreasing the varroa load continues to rise exponentially and the untreated colony can soon be overwhelmed, with fatal results. Apart from weakening the adult bees and shortening their lives, Varroa can cause them to suffer from a variety of serious virus infections including Deformed Wing Virus (DWV), Chronic Bee Paralysis Virus (CBPV) and more. There are numerous approved products on the market, some containing natural ingredients such as Formic Acid, Thymol and essential oils. Others are composed of manufactured chemicals including Amitraz, Flumethrin and Tau Fluvalinate. Artificial or ‘hard’ chemicals are effective but carry the risk of the varroa developing resistance.

Whilst Formic Acid treatments are said by some to be tough on the queens or cause excessive losses, all the authorized brands are safe to use if the manufacturer’s instructions are followed to the letter, especially regarding dosage, temperature and ventilation. All are designed to kill the mites that are feeding and reproducing inside the capped brood.

Treatment must be applied after removal of the supers containing honey for human consumption. Any supers left in place during treatment should be marked to indicate that they may contain traces of the miticide used and shouldn’t be used again until the frames have been cleaned and refitted with new foundation.

A second treatment of Oxalic Acid to kill the ‘phoretic’ mites, i.e. those living and feeding on the adult bees, is given in winter when there is little or no brood. Traditionally this was carried out in late December between Christmas and New Year, but recent research has shown that in Southern England the optimum period is now early December. Treatment is by trickling the dissolved product from a syringe, using a device called Gas Vap which is a modified blow torch, or by sublimation with special equipme nt. Treatment with Oxalic Acid requires the operator and any bystanders to wear personal protective equipment.

Queens

Apart from Varroa and its attendant diseases, queen failure is probably the second most common cause of winter losses. Queens are at their most productive in the first 2 years of their life. After that their egg laying capacity declines and they are likely to be superseded. Unfortunately, the chances of a replacement queen being mated are diminishing rapidly and both the old and the new queen will fail to survive.

Now is a good time to introduce new, mated queens which are ready to produce the vital winter bees needed to see the colony through winter and into spring. If the old queen has good genetic traits, and you can’t bear to part with her, she can be retired into a nuc and used for emergencies such as making up winter losses, or for raising new queens next year.

Young queens in their first 2 years are less inclined to swarm the following year. Those that do make swarm preparations will pass on the trait to their offspring and their drones will spread the swarmy behaviour to other colonies in the area. The colony should be requeened as soon as practicable.

Similarly, if the colony has been excessively defensive or flighty during the season, requeening now will improve the temperament of the colony and make your beekeeping a pleasure again, as well as not spreading the undesirable genes to other beekeepers stock by its drones.

Like humans, not all queens are born equal and poorly mated or badly developed queens will fail early in their lives or be superseded.

Pests and predators

Mouse guards and woodpeckers. Mice are sometimes tempted into hives at the start of winter by the prospect of a warm home in which to hibernate. Mouse guards fitted in October will deny them access. In a hard winter when there is little food available, green woodpeckers will drill holes in the side of hives and raid the contents causing considerable damage and often leaving the colony to die of cold or starvation. A cage of chicken wire around the hives will prevent the birds from attacking them.

Insulation

A layer of insulation in the roof of wooden hives can help to keep the cluster warm and reduce the quantity of stores they consume in order to produce heat. The winter bees are more rested and likely to live longer. Insulated hives enjoy better winter survival rates and faster spring build up. Poly hives and nucs have an advantage in this respect.

Summary

- A colony that is fit, strong and well fed, with a productive young queen, will have a better chance of getting through winter and spring.

- Bees born in August and September will die in October and November. Bees born in October will live until the following spring.

- Feeding of thin 1:1 sugar syrup in September will stimulate the queen to lay in October and produce the vitally important winter bees.

- Feeding of thick sugar syrup be laid down as stores.

- Feeding with fondant will see the colony through times when it is too cold for the bees to consume syrup.

- Varroa treatments in August and December are required to prevent winter and spring losses.

- Colonies led by young queens are much more likely to survive than those with older queens. They are also less susceptible to swarming the following spring.

- Protection against mice and woodpeckers is fitted in October.

- Insulation can make stores last longer, extend the life of the winter bees, and help the colony to grow faster in spring.

References:

BBKA Healthy Hive Guide

BBKA Special Edition: Feeding Honey Bees

Baxter A. https://www.alanbaxtersblogs.co.uk

National Bee Unit Managing Varroa https://shorturl.at/ysjpR

Stainton, K. (2022) Varroa Management: A Practical Guide on How to Manage Varroa Mites in Honey Bee Colonies, Northern Bee Books.

MAKING MEAD

We use all the wonderful produce of the hive ensuring that nothing is wasted. Among these is the production of Mead, a delicious type of wine made entirely with honey. Instead of swilling it down the drain we capture all the honey-rich rinsing water from the extractor and the other equipment, add yeast and put it in demijons to ferment, then wait. Simple as that!

The results are incredibly good, producing a luscious, golden drink full of the flavours of honey and with hints of citrus fruits. Here's our 2023 cuvée:

APIARY TRAINING DAY 7 JULY 2024

The day was divided into two sessions, one for beginners and beekeepers with less than 2 years experience and the second for improvers and those preparing for the BBKA Basic Assessment. The programme was built around the following topics:

BEGINNERS

The aims were:

To carry out a safe, efficient inspection with confidence, to recognise the signs of swarm preparation and actions to take. Finding a queen, practice good apiary hygiene procedures. We also covered lighting the smoker, basic inspections, hive tool handling, use of smoke, keeping the colony under control, reading the colony, the countdown to swarming and the logic of swarm prevention and control. The dangers of varroa were discussed and drone brood uncapping demonstrated.

Despite torrential rain showers and the threat of thunderstorms which unsettled the bees, the session went smoothly and the objectives achieved.

IMPROVERS

The aims of this session were:

To carry out efficient health inspection, describe brood & adult bee diseases, methods of varroa IPM and treatment, understand the countdown to swarming and take appropriate action.

The bees were becoming increasingly agitated due to the weather and the sudden interruption of the summer nectar flow but the objectives were achieved. One colony was found to have some evidence of chalk brood and one or two examples of Deformed Wing Virus were noted. The signs of all the main adult and brood diseases were described and the recommended treatments discussed. A Pagden artificial swarm was carried out and the Heddon Variant was explained. The technique of obtaining drawn comb in a flow was observed. IPM by drone brood uncapping and drone brood sacrifice were seen as well as counting the drop on the varroa board, sugar roll and alcohol wash, and calculating the percentage infestation using the NBU calculator.

CONCLUSIONS

It is useful to divide into two groups of different levels of experience.

Rain can be dealt with but stormy conditions and interruption in the nectar flow are unsettling for the bees with the risk of grumpiness, even in the calmest of colonies.

QUEEN INTRODUCTION

It’s the time of year when beekeepers are buying in new queens and are faced with the uncertainty of whether or not the queen will be accepted in her new colony. The following method was first described by L.E. Snelgrove (1) in 1940 who claimed an almost 100% success rate.

The method is based on the principle that the new queen should adopt the receiving colony’s odour before being introduced.

The colony should be showing signs of queenlessness before carrying out the operation; this usually takes from a few minutes to as much as half an hour after removal of the old queen.

The “one-hour’’ method

-

Release the bees escorting the new queen from the cage in which they arrived.

-

Take a matchbox and place it three-quarters open over brood comb in the receiving

colony at a point where the bees are thickest.

-

Gently close it with about 20 bees inside.

-

Put a pin through the side to keep it closed and put it in your pocket for 5 to 10

minutes.

-

At the end of this period partly open the box with your thumb over the opening and

drop the new queen in among the bees.

-

Close the box leaving a very narrow opening for ventilation, put in the pin and return

it to your pocket for half an hour.

-

The bees confined in the dark with no food will be more interested in trying to get out than the presence of the new queen.

-

The queen and the bees will soon have the same odour thanks to the warmth in your pocket.

-

Give a little whiff of smoke through the hole in the crown board to clear the way.

-

Place the matchbox upside down over the hole in the crown board and open it gently

-

The new queen and her new escort will then safely make their way down into the

queenless hive.

-

Close the hive and don’t disturb for a few days.

Essential points :

• The queen acquires the odour of the hive before being introduced.

• She is hungry when she enters the hive.

• She enters the hive accompanied by a friendly escort.

• The hive is in a state of distress and looking anxiously for their queen.(1) L.E. Snelgrove The Introduction of Queen Bees Furnell & Sons Aug 1940

Alan Baxter 21 April 2024

NOSEMA

There have been many reports of winter and spring colony losses this year for which there could be any number of causes. One answer to the mysterious death of a previously productive colony is infection with a microsporidian, or spore-forming pathogen, called Nosema.

Two types have been identified in Britain, N.apis and N. ceranae. They are similar in many ways but the main difference between them is the seasonal nature of their impact on colonies. N.apis can almost disappear in summer wheras N. ceranae is active throughout the year and its impact is often more severe as a result.

What does it do?

Nosema affects the ability of the larva and the adult bee to absorb nutrients, shortening its life and preventing the winter bees from surviving until the following spring. They are also unable to produce enough brood food for the larvae resulting either death or a slow buildup of the colony.

There are often no obvious signs of infection, although occasionally it is accompanied by dysentery, in which case there may be staining around the entrance and on top of the frames.

How do you know you’ve got it?

Diagnosis is by laboratory analysis, but you can carry out a rough test in the apiary:

-

Take a few young bees from the centre of the brood nest and kill them

-

With forceps gently pull out the intestines from where they exit the body near the sting

area.

-

The midgut, which is normally brownish in colour, in the infected bee is white and

often distended.

To confirm the infection, take a sample of 30 bees from the centre of the brood nest and euthanize them in the freezer and send them to someone with a microscope for analysis. If you have your own microscope it’s quite simple:

-

Cut off the abdomens and crush them in a mortar and pestle. Add a few drops of distilled water and stir.

-

Take a drop of the soup and place it on a slide. Allow to dry

-

Examine under a compound microscope at x 400. Nosema spores look like the image below.

-

How do you treat it?

There is no specific treatment for Nosema but it can be reduced by strict apiary hygiene, feeding and comb change. A less stressful method is a Bailey Comb Change for a weak colony. In some cases changing the queen can be effective.

Bailey comb change for a weak colony

-

Place a clean brood box beside the colony

-

Find the frame with the queen and place in the new brood box

-

Add a frame of sterilized drawn comb either side of the frame with the queen

-

Add dummy boards either side and centre them

-

In the original brood box remove any frames with no brood and destroy the comb

-

Centre the remaining frames with dummy boards

-

Close the entrance

-

Add a Bailey board

-

Put the new box on top

-

Add a feeder with sugar syrup

-

Close the hive

Day 8

-

From the original brood box remove all frames with no brood

-

From the new box remove the frame that had the queen and place in the lower box

-

Centre the frames so they chimney upwards

-

Add more frames of drawn comb to the upper box

-

Check feed and top up if necessary

Day 15

-

Repeat as above

-

Day 28

-

All the brood in the original box will have emerged and the box can be removed

-

Put the new box on a new floor on the original stand

-

Add any supers

-

Close the hive

All the old comb should be burnt and the brood box and frames cleaned and sterilized for reuse.

Alan Baxter April 2024

Signs of dysentery Nosema spores

Bailey Comb Change for a weak colony

23 March 2024

Another milestone today. It was the final theory examination for the Master Beekeeper Qualification, results in early May.

BE PREPARED FOR SWARMING

The swarming season has been particularly intense this year due to a long, cool spring followed by a sudden spell of warm weather. Although the worst seems to be over there are still some swarms around and the season is by no means over so there is no room for complacency.

In an earlier blog I talked about the basic theory of swarming and some of the measures you can take to prevent or control it. In this paper I’ll expand on the mechanics and timings of swarming, the differences between prevention and control and the precautions to take against casts or secondary swarms.

In order to deal with the ever-present threat of losing half your bees and terrorizing your neighbours, it’s useful to understand the swarming process, the key indicators to look out for and the prevention or control measures you can take.

In the chart below you will see the progression that occurs. I’ve divided it into two parts – the times when you can take prevention measures, and those when control is necessary.

Prevention

Prevention requires regular, thorough inspections and careful observation, at least weekly unless your queens are clipped in which case every 10 days will do. Anticipate and act are the key words.

Here are some simple but effective measures you can take:

- Mark your queens

- If you can’t find the queen get another pair of eyes or two to help you

- The earlier in the season the better when there aren’t too many bees

- Do it in the warmest part of the day when the maximum number of bees are out foraging

- Or move the brood box to one side and put a super on its original stand to divert all the flying bees and give you more room and quiet to look.

- Clip your queens. This involves gently cutting off the end third of one wing. It isn’t to everyone’s taste but there are no nerves or blood vessels there – it’s like cutting your toenails.

If you’re struggling with any of these, get a more experienced beekeeper to help you. People are always happy to lend a hand.

- Give them more space by adding supers early

- The bees need room to live and to store incoming nectar and pollen

- Nectar contains about 80% water and requires a greater volume of space than honey which only contains 20% or less

- The queen needs more space to lay her eggs

- Add a super as soon as the brood box starts to look crowded. When the flow starts they will be bringing in nectar very fast

- If there are no supers they will store nectar in the brood box, thereby depriving the queen of laying space and the workers of living room

- Remember that during the day, a lot of the bees will be out foraging. At night they need somewhere to sleep

- Replace surplus frames of honey with drawn comb or foundation

- Replace damaged comb which can’t be used efficiently

- Have your equipment ready in advance to take off the pressure when the time comes to act.

Control

Once the queen cells have been formed, the time for prevention has passed and control measures are needed. I prefer to use either the nuc or the Pagden method if I want to make increase from the colony, or the Demaree technique if I don’t want any more hives or to breed from that particular queen. All three are described in my earlier blog or can be found on numerous websites and on YouTube.

Beware the cast or secondary swarm

After the first swarm has issued, all the sealed brood that the queen had been producing in the period before the swarm will start to emerge (remember those big slabs of brood about 3 weeks ago?). This could mean that newly-emerged virgin queens might trigger another swarm.

To reduce the risk of secondary swarming:

- remove all the sealed queen cells

- choose the best two unsealed ones, marking their position on the frame with a drawing pin

- One week later go back and remove any more queen cells that have been made and

- remove one of the marked ones

- Make notes in your hive records of the dates – it can take longer than you think for a new queen to be mated and start to lay.

Don’t be beguiled into thinking that your colony haven’t swarmed because the hive is still full of bees – it’s all that brood emerging after the main swarm has left.

If they have swarmed, treat it as the parent colony and remove all the queen cells except one. Don’t be tempted to leave a second one as belt and braces.

Happy beekeeping!

Enormous thanks to Christine Coulsting, Master Beekeeper, for her excellent guidance on this and many other topics.

by Alan Baxter

POLLEN PATTIES – TO FEED OR NOT TO FEED

There is a lot of controversy about the feeding of pollen in spring.

We all want to do the best for our bees, including making sure that, having survived the winter, they don’t succumb to spring starvation. We know there is very little forage available, but we see our bees becoming increasingly active on warmer days and we suspect the queens are already laying. Newly-emerged brood will soon be demanding to be fed. Worker larvae need lots of protein and protein comes from pollen, but do they have enough pollen stores and are the foragers finding enough sources of early pollen around? Snowdrop, crocus, willow, hazel….?

So being caring, responsible beekeepers we top up the fondant and add a dollop of pollen mixture to the feed. We are careful to make sure that the product we buy is of good quality and that the ingredients are digestible by the bees without upsetting their tummies.

But is it really a good idea? Or is it even necessary? There are different schools of thought, widely varying in their opinions, but briefly they go like this:

The pro-pollen feeders:

- Feeding pollen will stimulate rapid spring build-up so the colony has a maximum workforce for the spring nectar flow, especially in areas where there is OSR.

- The queen has already started to lay and needs all the help she can get if healthy, well-fed workers are to be produced.

- Let’s give them some just in case and because it’s a ‘good thing’ to do.

The anti-pollen feeders may argue:

- The colony will develop or not in the spring according to the availability of food. This is the way that bees have evolved, to be in synch with the natural rhythm of the seasons.

- If we encourage the queen to start laying early, when the brood emerges there won’t be enough forage to sustain the growing population and more artificial feeding will be needed.

- An early boost in the amount of brood requiring care will outnumber the nurse bees needed to look after them, and the brood will either die of starvation or develop into undernourished, smaller, weaker adults.

- Winter bees nearing the end of their lives, but still needed for colony survival, will be required to do more work than they are capable of and will die earlier, leaving the colony short.

- We want our bees to adapt to changing climatic conditions, and by feeding them artificially we will only delay their ability to evolve, thereby making them more dependent on us.

For me the jury is still out and I’d welcome any thoughts members have on this topic.

by Alan Baxter

SPRING FIRST INSPECTION

I wouldn’t normally open my hives until the temperature reaches tee-shirt level. It’s not worth the risk of chilling the colony or accidentally harming the queen with no chance of the colony being able to replace her.

In case of doubt, especially if you’re new to beekeeping, it’s better to wait for another week or so until the weather is consistently better.

However, it managed to get up to 14 degrees for a few hours on Thursday in my sheltered south-facing home apiary and I carried out very quick first inspections, mainly to check for early signs of swarming. All was well except for one colony which appears to have a mixture of normal worker brood and a high proportion of drone brood.

I suspect it’s a failing queen despite her being less than a year old. This is a colony that suffered an attack of heavy robbing last year and never recovered its original vigour.

There are options :

- 1. Kill the queen and unite them as they are with another colony

- 2. Destroy the queen and all the drone brood, together with any varroa, then unite them

- 3. Squidge the queen and give them a frame of brood from another colony

- 4. Shake them out and let the bees take their chance begging for admission to the other hives

- 5. Let nature take its course, allow the brood to hatch and see what happens.

Factors to consider:

- There are only 4 frames of bees

- Most of them will be winter bees nearing the end of their lives

- There won’t be enough nurse bees to tend to the emerging larvae

- Drones are a drain on the colony’s resources at this time of the year, whilst giving nothing back in return.

The remaining workers might be useful to a receiving colony if:

- their hypopharyngeal glands are still active and they’re able to produce brood food or

- they could add to the foraging force

These benefits are likely to be short-lived for the reasons stated above.

Any new queens produced this early in the season would struggle to get mated.

My preferred option is No: 2. This offers me the opportunity to give another colony a temporary boost and to carry out a bit of varroa control at the same time, but I would love to hear what other members think.

by Alan Baxter February 2023